Resolving and Binding

Once in a while you find yourself in an odd situation. You get into it by degrees and in the most natural way but, when you are right in the midst of it, you are suddenly astonished and ask yourself how in the world it all came about.

Thor Heyerdahl, Kon-Tiki

Oh, no! Our language implementation is taking on water! Way back when we added variables and blocks, we had scoping nice and tight. But when we later added closures, a hole opened in our formerly waterproof interpreter. Most real programs are unlikely to slip through this hole, but as language implementers, we take a sacred vow to care about correctness even in the deepest, dampest corners of the semantics.

We will spend this entire chapter exploring that leak, and then carefully patching it up. In the process, we will gain a more rigorous understanding of lexical scoping as used by Lox and other languages in the C tradition. We’ll also get a chance to learn about semantic analysis—a powerful technique for extracting meaning from the user’s source code without having to run it.

11 . 1Static Scope

A quick refresher: Lox, like most modern languages, uses lexical scoping. This means that you can figure out which declaration a variable name refers to just by reading the text of the program. For example:

var a = "outer"; { var a = "inner"; print a; }

Here, we know that the a being printed is the variable declared on the

previous line, and not the global one. Running the program doesn’t—can’t—affect this. The scope rules are part of the static semantics of the language,

which is why they’re also called static scope.

I haven’t spelled out those scope rules, but now is the time for precision:

A variable usage refers to the preceding declaration with the same name in the innermost scope that encloses the expression where the variable is used.

There’s a lot to unpack in that:

-

I say “variable usage” instead of “variable expression” to cover both variable expressions and assignments. Likewise with “expression where the variable is used”.

-

“Preceding” means appearing before in the program text.

var a = "outer"; { print a; var a = "inner"; }

Here, the

abeing printed is the outer one since it appears before theprintstatement that uses it. In most cases, in straight line code, the declaration preceding in text will also precede the usage in time. But that’s not always true. As we’ll see, functions may defer a chunk of code such that its dynamic temporal execution no longer mirrors the static textual ordering. -

“Innermost” is there because of our good friend shadowing. There may be more than one variable with the given name in enclosing scopes, as in:

var a = "outer"; { var a = "inner"; print a; }

Our rule disambiguates this case by saying the innermost scope wins.

Since this rule makes no mention of any runtime behavior, it implies that a variable expression always refers to the same declaration through the entire execution of the program. Our interpreter so far mostly implements the rule correctly. But when we added closures, an error snuck in.

var a = "global"; { fun showA() { print a; } showA(); var a = "block"; showA(); }

Before you type this in and run it, decide what you think it should print.

OK . . . got it? If you’re familiar with closures in other languages, you’ll expect

it to print “global” twice. The first call to showA() should definitely print

“global” since we haven’t even reached the declaration of the inner a yet. And

by our rule that a variable expression always resolves to the same variable,

that implies the second call to showA() should print the same thing.

Alas, it prints:

global block

Let me stress that this program never reassigns any variable and contains only a

single print statement. Yet, somehow, that print statement for a

never-assigned variable prints two different values at different points in time.

We definitely broke something somewhere.

11 . 1 . 1Scopes and mutable environments

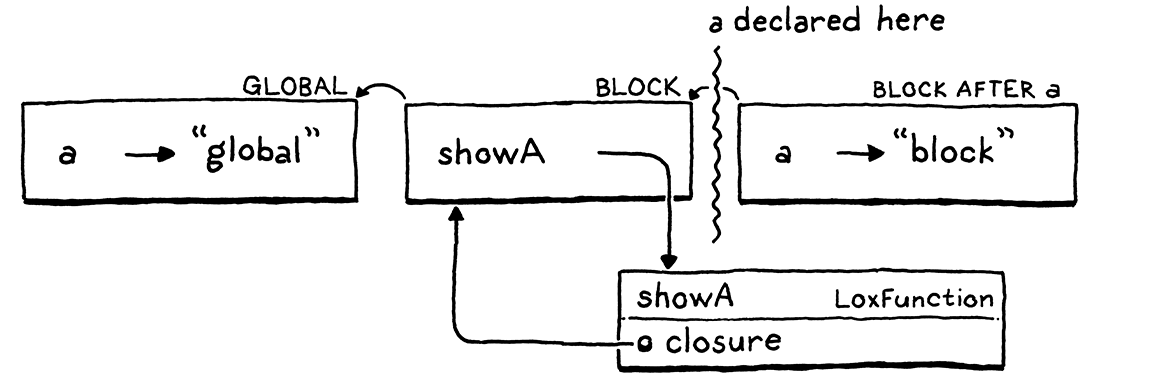

In our interpreter, environments are the dynamic manifestation of static scopes. The two mostly stay in sync with each other—we create a new environment when we enter a new scope, and discard it when we leave the scope. There is one other operation we perform on environments: binding a variable in one. This is where our bug lies.

Let’s walk through that problematic example and see what the environments look

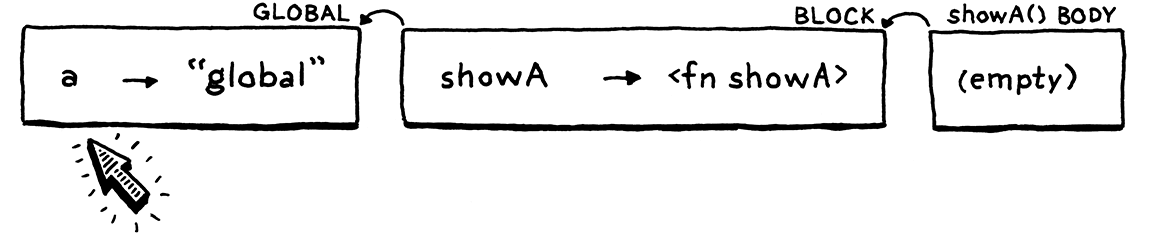

like at each step. First, we declare a in the global scope.

That gives us a single environment with a single variable in it. Then we enter

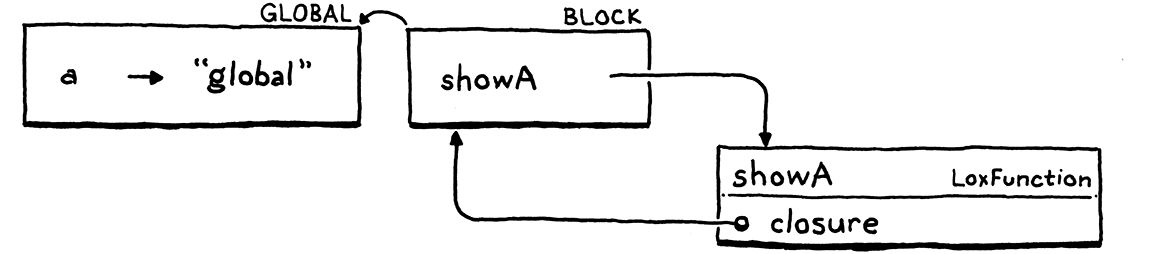

the block and execute the declaration of showA().

We get a new environment for the block. In that, we declare one name, showA,

which is bound to the LoxFunction object we create to represent the function.

That object has a closure field that captures the environment where the

function was declared, so it has a reference back to the environment for the

block.

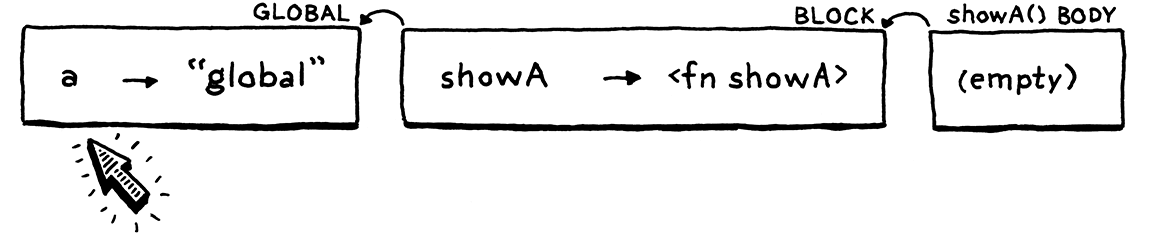

Now we call showA().

The interpreter dynamically creates a new environment for the function body of

showA(). It’s empty since that function doesn’t declare any variables. The

parent of that environment is the function’s closure—the outer block

environment.

Inside the body of showA(), we print the value of a. The interpreter looks

up this value by walking the chain of environments. It gets all the way to the

global environment before finding it there and printing "global". Great.

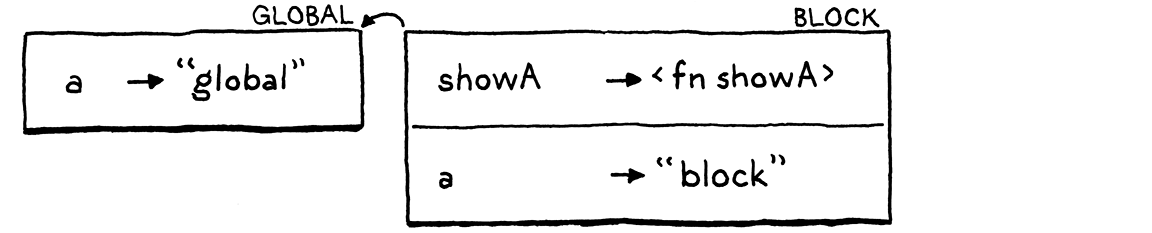

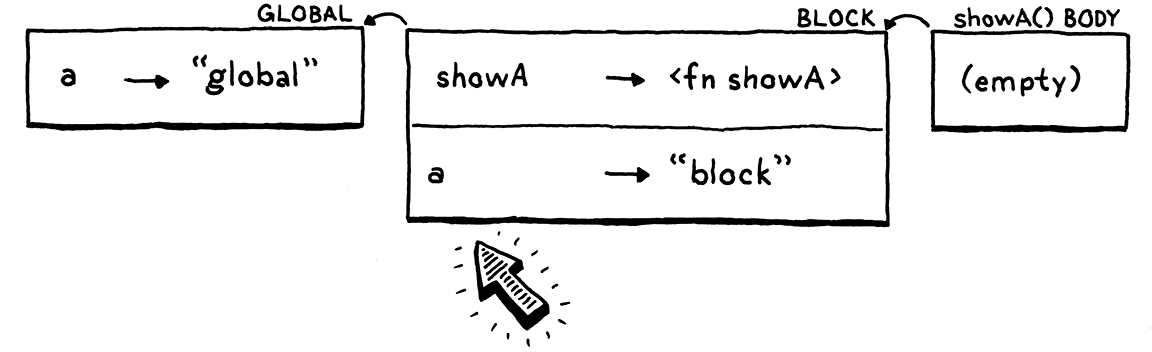

Next, we declare the second a, this time inside the block.

It’s in the same block—the same scope—as showA(), so it goes into the

same environment, which is also the same environment showA()’s closure refers

to. This is where it gets interesting. We call showA() again.

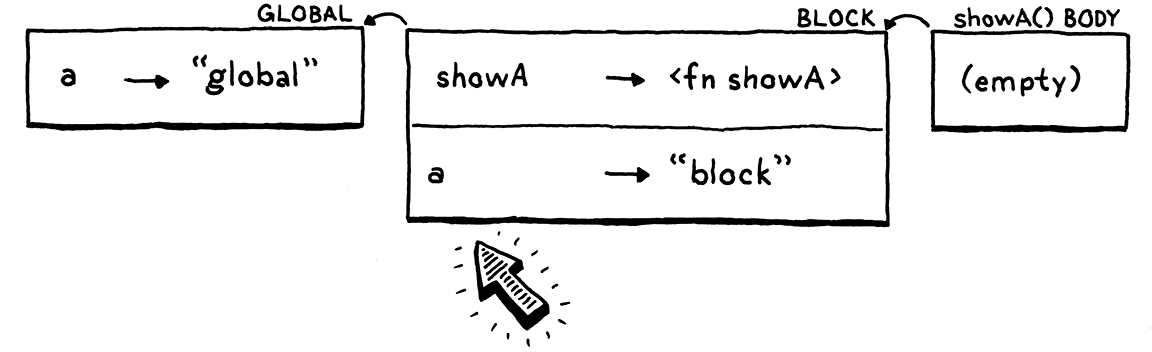

We create a new empty environment for the body of showA() again, wire it up to

that closure, and run the body. When the interpreter walks the chain of

environments to find a, it now discovers the new a in the block

environment. Boo.

I chose to implement environments in a way that I hoped would agree with your informal intuition around scopes. We tend to consider all of the code within a block as being within the same scope, so our interpreter uses a single environment to represent that. Each environment is a mutable hash table. When a new local variable is declared, it gets added to the existing environment for that scope.

That intuition, like many in life, isn’t quite right. A block is not necessarily all the same scope. Consider:

{

var a;

// 1.

var b;

// 2.

}

At the first marked line, only a is in scope. At the second line, both a and

b are. If you define a “scope” to be a set of declarations, then those are

clearly not the same scope—they don’t contain the same declarations. It’s

like each var statement splits the block into two

separate scopes, the scope before the variable is declared and the one after,

which includes the new variable.

But in our implementation, environments do act like the entire block is one scope, just a scope that changes over time. Closures do not like that. When a function is declared, it captures a reference to the current environment. The function should capture a frozen snapshot of the environment as it existed at the moment the function was declared. But instead, in the Python code, it has a reference to the actual mutable environment object. When a variable is later declared in the scope that environment corresponds to, the closure sees the new variable, even though the declaration does not precede the function.

11 . 1 . 2Persistent environments

There is a style of programming that uses what are called persistent data structures. Unlike the squishy data structures you’re familiar with in imperative programming, a persistent data structure can never be directly modified. Instead, any “modification” to an existing structure produces a brand new object that contains all of the original data and the new modification. The original is left unchanged.

If we were to apply that technique to Environment, then every time you declared a variable it would return a new environment that contained all of the previously declared variables along with the one new name. Declaring a variable would do the implicit “split” where you have an environment before the variable is declared and one after:

A closure retains a reference to the Environment instance in play when the function was declared. Since any later declarations in that block would produce new Environment objects, the closure wouldn’t see the new variables and our bug would be fixed.

This is a legit way to solve the problem, and it’s the classic way to implement environments in Scheme interpreters. We could do that for Lox, but it would mean going back and changing a pile of existing code.

I won’t drag you through that. We’ll keep the way we represent environments the same. Instead of making the data more statically structured, we’ll bake the static resolution into the access operation itself.

11 . 2Semantic Analysis

Our interpreter resolves a variable—tracks down which declaration it refers to—each and every time the variable expression is evaluated. If that variable is swaddled inside a loop that runs a thousand times, that variable gets re-resolved a thousand times.

We know static scope means that a variable usage always resolves to the same declaration, which can be determined just by looking at the text. Given that, why are we doing it dynamically every time? Doing so doesn’t just open the hole that leads to our annoying bug, it’s also needlessly slow.

A better solution is to resolve each variable use once. Write a chunk of code that inspects the user’s program, finds every variable mentioned, and figures out which declaration each refers to. This process is an example of a semantic analysis. Where a parser tells only if a program is grammatically correct (a syntactic analysis), semantic analysis goes farther and starts to figure out what pieces of the program actually mean. In this case, our analysis will resolve variable bindings. We’ll know not just that an expression is a variable, but which variable it is.

There are a lot of ways we could store the binding between a variable and its declaration. When we get to the C interpreter for Lox, we’ll have a much more efficient way of storing and accessing local variables. But for pylox, I want to minimize the collateral damage we inflict on our existing codebase. I’d hate to throw out a bunch of mostly fine code.

Instead, we’ll store the resolution in a way that makes the most out of our

existing Environment class. Recall how the accesses of a are interpreted in

the problematic example.

In the first (correct) evaluation, we look at three environments in the chain

before finding the global declaration of a. Then, when the inner a is later

declared in a block scope, it shadows the global one.

The next lookup walks the chain, finds a in the second environment and stops

there. Each environment corresponds to a single lexical scope where variables

are declared. If we could ensure a variable lookup always walked the same

number of links in the environment chain, that would ensure that it found the

same variable in the same scope every time.

To “resolve” a variable usage, we only need to calculate how many “hops” away the declared variable will be in the environment chain. The interesting question is when to do this calculation—or, put differently, where in our interpreter’s implementation do we stuff the code for it?

Since we’re calculating a static property based on the structure of the source code, the obvious answer is in the parser. That is the traditional home, and is where we’ll put it later in clox. It would work here too, but I want an excuse to show you another technique. We’ll write our resolver as a separate pass.

11 . 2 . 1A variable resolution pass

After the parser produces the syntax tree, but before the interpreter starts executing it, we’ll do a single walk over the tree to resolve all of the variables it contains. Additional passes between parsing and execution are common. If Lox had static types, we could slide a type checker in there. Optimizations are often implemented in separate passes like this too. Basically, any work that doesn’t rely on state that’s only available at runtime can be done in this way.

Our variable resolution pass works like a sort of mini-interpreter. It walks the tree, visiting each node, but a static analysis is different from a dynamic execution:

-

There are no side effects. When the static analysis visits a print statement, it doesn’t actually print anything. Calls to native functions or other operations that reach out to the outside world are stubbed out and have no effect.

-

There is no control flow. Loops are visited only once. Both branches are visited in

ifstatements. Logic operators are not short-circuited.

11 . 3A Resolver Function

Our variable resolution pass works similarly to the eval/exec methods of our

interpreter. It is, afterall, a kind of abstract interpretation—one that only

simulates the overall structure of execution, tracking variable definitions and

usage without actually running each command in detail.

Like we did before, the resolver module exposes one simple function that implements the main functionality in the resolution pass.

# lox/resolver.py import copy from functools import singledispatch from lox.ast import * def resolve(program: Program) -> Program: env = Env() program = copy.deepcopy(program) resolve_node(program, env) if env.errors: raise LoxStaticError(env.errors) return program

The resolver initializes a new environment to track scopes and then delegates

the work to a helper function, resolve_node(), which is implemented as a

singledispatch method.

# lox/resolver.py @singledispatch def resolve_node(node: Expr | Stmt, env: Env) -> None: for child in vars(node).values(): if isinstance(child, (Stmt, Expr, list)): resolve_node(child, env)

Differently from before, resolve_node() has a useful generic implementation.

It uses Python’s reflection capabilities to walk all of the fields of the given

node, resolving them recursivelly.

It can handle Expr, Stmt and we sneak support for Python lists to simplify the implementation of a few nodes:

# lox/resolver.py after resolve_node() @resolve_node.register def _(stmts: list, env: Env) -> None: for stmt in stmts: resolve_node(stmt, env)

The resolver needs to visit every node in the syntax tree, but only a few kinds of nodes are interesting when it comes to resolving variables:

-

A block statement introduces a new scope for the statements it contains.

-

A function declaration introduces a new scope for its body and binds its parameters in that scope.

-

A variable declaration adds a new variable to the current scope.

-

Variable and assignment expressions need to have their variables resolved.

The rest of the nodes don’t do anything special, and the fallback implementation takes good care of them.

11 . 3 . 1Resolving Environment

The resolver visits each node in the syntax tree, tracking variable definitions

and usage. This information must be stored somewhere, to give it some context to

modify the syntax tree accordingly. Our Env class seems like a natural fit for

the job, but we need to extend it a bit.

# lox/resolver.py after imports from lox import env from dataclasses import dataclass, field from typing import Literal as Enum from lox.errors import LoxSyntaxError from lox.ast import * type Binding = Enum["DECLARED", "DEFINED"] @dataclass class Env(env.Env[Binding]): errors: list[Exception] = field(default_factory=list)

For now, we specify the type of bindings and add a list to store any errors we encounter during resolution. The resolver doesn’t track variable values—that would require that we actually run the program—so we use a simple enum to track the state of each variable in the scope maps.

- A DECLARED variable has been declared in the current scope, but its initializer has not yet been resolved.

- A DEFINED variable has been fully initialized and is ready for use.

We also track errors just like we did in the Parser:

# lox/resolver.py Env method def error(self, token: Token, message: str) -> Exception: error = LoxSyntaxError.from_token(token, message) self.errors.append(error) return error

Finally, we modify Env.push() to make the enclosed enviroment share the same

list of errors as its parent.

# lox/resolver.py Env method def push(self) -> Env: return Env(self, errors=self.errors)

11 . 3 . 2Resolving blocks

We start with blocks since they create the local scopes where all the magic happens.

# lox/resolver.py after resolve_node() @resolve_node.register def _(stmt: Block, env: Env) -> None: resolve_node(stmt.statements, env.push())

This begins a new scope and traverses into the statements inside the block using

this nested scope. It tranverses the list of statements since we implemented

support for lists in the generic resolve_node() method.

Lexical scopes nest in both the interpreter and the resolver. They behave like a stack. We implement that stack using a linked list—the chain of Env objects.

The scope stack is only used for local block scopes. Variables declared at the top level in the global scope are not tracked by the resolver since they are more dynamic in Lox. When resolving a variable, if we can’t find it in the stack of local scopes, we assume it must be global.

11 . 3 . 3Resolving variable declarations

Resolving a variable declaration adds a new entry to the current innermost scope’s map. That seems simple, but there’s a little dance we need to do.

# lox/resolver.py after resolve_node() @resolve_node.register def _(stmt: Var, env: Env) -> None: env.declare(stmt.name) if stmt.initializer is not None: resolve_node(stmt.initializer, env) env.define(stmt.name)

We split binding into two steps, declaring then defining, in order to handle funny edge cases like this:

var a = "outer"; { var a = a; }

What happens when the initializer for a local variable refers to a variable with the same name as the variable being declared? We have a few options:

-

Run the initializer, then put the new variable in scope. Here, the new local

awould be initialized with “outer”, the value of the global one. In other words, the previous declaration would desugar to:var temp = a; // Run the initializer. var a; // Declare the variable. a = temp; // Initialize it.

-

Put the new variable in scope, then run the initializer. This means you could observe a variable before it’s initialized, so we would need to figure out what value it would have then. Probably

nil. That means the new localawould be re-initialized to its own implicitly initialized value,nil. Now the desugaring would look like:var a; // Define the variable. a = a; // Run the initializer.

-

Make it an error to reference a variable in its initializer. Have the interpreter fail either at compile time or runtime if an initializer mentions the variable being initialized.

Do either of those first two options look like something a user actually wants? Shadowing is rare and often an error, so initializing a shadowing variable based on the value of the shadowed one seems unlikely to be deliberate.

The second option is even less useful. The new variable will always have the

value nil. There is never any point in mentioning it by name. You could use an

explicit nil instead.

Since the first two options are likely to mask user errors, we’ll take the third. Further, we’ll make it a compile error instead of a runtime one. That way, the user is alerted to the problem before any code is run.

In order to do that, as we visit expressions, we need to know if we’re inside the initializer for some variable. We do that by splitting binding into two steps. The first is declaring it.

We implement some helper methods to avoid fiddling with the maps directly.

# lox/resolver.py Env method def declare(self, name: Token) -> None: if not self.enclosing: return self[name.lexeme] = "DECLARED"

Declaration adds the variable to the innermost scope so that it shadows any

outer one and so that we know the variable exists. We mark it as “not ready yet”

by binding its name to "DECLARED" in the scope map. The value associated with

a key in the scope map represents whether or not we have finished resolving that

variable’s initializer.

After declaring the variable, we resolve its initializer expression in that same scope where the new variable now exists but is unavailable. Once the initializer expression is done, the variable is ready for prime time. We do that by defining it.

# lox/resolver.py Env method def define(self, name: Token) -> None: if not self.enclosing: return self[name.lexeme] = "DEFINED"

We set the variable’s value in the scope map to "DEFINED" to mark it as fully

initialized and available for use. It’s alive!

11 . 3 . 4Resolving variable expressions

Variable declarations—and function declarations, which we’ll get to—write to the scope maps. Those maps are read when we resolve variable expressions.

# lox/resolver.py after resolve_node() @resolve_node.register def _(expr: Variable, env: Env) -> None: if env.values.get(expr.name.lexeme) == "DECLARED": msg = "Can't read local variable in its own initializer." env.error(expr.name, msg) resolve_local(expr, expr.name, env)

First, we check to see if the variable is being accessed inside its own

initializer. This is where the values in the scope map come into play. If the

variable exists in the current scope but its value is "DECLARED", that means

we have declared it but not yet defined it. We report that error.

After that check, we actually resolve the variable itself using this helper:

# lox/resolver.py def resolve_local(expr: Expr, name: Token, env: Env) -> None: expr.depth = env.get_depth(name.lexeme)

Which stores the depth of the variable in the syntax tree node itself. This requires some tweaking to our syntax trees.

# lox/ast.py Variable add field ... depth: int = -1

The new depth field stores how many scopes away the variable’s declaration is

from the current innermost scope. A depth of 0 means the variable is in the

current scope. A depth of 1 means it’s in the immediately enclosing scope, and

so on. Negative depths are sentinels meaning the variable is still unresolved.

resolve_local() also uses a new method in our Env class to calculate that

depth:

# lox/resolver.py Env method def get_depth(self, name: str) -> int: if name in self.values or self.enclosing is None: return 0 return 1 + self.enclosing.get_depth(name)

This looks, for good reason, a lot like the code in Env for evaluating a variable. We start at the innermost scope and work outwards, looking in each map for a matching name. If we find the variable, we resolve it, passing in the number of scopes between the current innermost scope and the scope where the variable was found. So, if the variable was found in the current scope, we pass in 0. If it’s in the immediately enclosing scope, 1. You get the idea.

11 . 3 . 5Resolving assignment expressions

The other expression that references a variable is assignment. Resolving one looks like this:

# lox/resolver.py after resolve_node() @resolve_node.register def _(expr: Assign, env: Env) -> None: resolve_node(expr.value, env) resolve_local(expr, expr.name, env)

First, we resolve the expression for the assigned value in case it also contains

references to other variables. Then we use our existing resolve_local()

function to resolve the variable that’s being assigned to.

Like before, we also need to add a depth field to the Assign syntax tree

node:

# lox/ast.py Assign add field ... depth: int = -1

11 . 3 . 6Resolving function declarations

Finally, functions. Functions both bind names and introduce a scope. The name of the function itself is bound in the surrounding scope where the function is declared. When we step into the function’s body, we also bind its parameters into that inner function scope.

# lox/resolver.py after resolve_node() @resolve_node.register def _(stmt: Function, env: Env) -> None: env.declare(stmt.name) env.define(stmt.name) resolve_function(stmt, "FUNCTION", env)

Similar to resolve_node(Variable), we declare and define the name of the

function in the current scope. Unlike variables, though, we define the name

eagerly, before resolving the function’s body. This lets a function recursively

refer to itself inside its own body.

Then we resolve the function’s body using this:

# lox/resolver.py after resolve_node() def resolve_function(function: Function, context: FunctionContext, env: Env) -> None: env = env.push(function_context=context) for param in function.params: env.declare(param) env.define(param) resolve_node(function.body, env)

It’s a separate function since we will also use it for resolving Lox methods when we add classes later. It creates a new scope for the body and then binds variables for each of the function’s parameters.

The extra parameter type is there to track what kind of function we’re

resolving. Right now, we only have one kind, but later we’ll add support for

methods and initializers. Some of those have special rules around return

statements that we’ll need to enforce during resolution. We need to declare this

type alias somewhere:

# lox/resolver.py after imports type FunctionContext = Enum["FUNCTION", None]

The Env class also must keep track if the current block is enclosed by a

function or not:

# lox/resolver.py Env field function_context: FunctionContext = None

Once that’s ready, it resolves the function body in that scope. This is different from how the interpreter handles function declarations. At runtime, declaring a function doesn’t do anything with the function’s body. The body doesn’t get touched until later when the function is called. In a static analysis, we immediately traverse into the body right then and there.

11 . 3 . 7Accessing a resolved variable

Our interpreter now has access to each variable’s resolved location. Finally, we get to make use of that. We replace eval(Variable) with this:

# lox/interpreter.py eval(Variable) # Replace return statement ... return env.get_at(expr.depth, expr.name.lexeme) ...

Instead of calling env[], we call this new method on Env:

# lox/env.py Env method def get_at(self, depth: int, name: str) -> T: while depth > 0: self = self.enclosing depth -= 1 if name in self.values: return self.values[name] raise NameError(name)

The old __getitem__() method dynamically walks the chain of enclosing

environments, scouring each one to see if the variable might be hiding in there

somewhere. But now we know exactly which environment in the chain will have the

variable.

This walks a fixed number of hops up the parent chain and returns the variable in there. It doesn’t even have to check to see if the variable is there—we know it will be because the resolver already found it before.

11 . 3 . 8Assigning to a resolved variable

We can also use a variable by assigning to it. The changes to interpreting an assignment expression are similar.

# lox/interpreter.py eval(Assign) # Replace call to env.assign() ... env.assign_at(expr.depth, expr.name.lexeme, value) ...

Again, we look up the variable’s scope distance and call a new setter method:

# lox/env.py Env method def assign_at(self, depth: int, name: str, value: T) -> None: while depth > 0: self = self.enclosing depth -= 1 if name not in self.values: raise NameError(name) self.values[name] = value

As get_at() is to __getitem__(), assign_at() is to assign(). It walks a

fixed number of environments, and then stuffs the new value in that map.

Those are the only changes to the interpreter functions. This is why I chose a representation for our resolved data that was minimally invasive. All of the rest of the nodes continue working as they did before. Even the code for modifying environments is unchanged.

11 . 3 . 9Running the resolver

We do need to actually run the resolver, though. We insert the new pass after the parser does its magic.

# lox/__main__.py Lox.run() # After ast = parse(tokens) ... ast = resolve(ast) ...

And don’t forget to import the resolve() function for this to work:

# lox/__main__.py after imports from lox.resolver import resolve

Simple, isnt it? The resolver is just another step in the pipeline from source code to execution.

11 . 4Resolution Errors

Since we are doing a semantic analysis pass, we have an opportunity to make Lox’s semantics more precise, and to help users catch bugs early before running their code. Take a look at this bad boy:

fun bad() { var a = "first"; var a = "second"; }

We do allow declaring multiple variables with the same name in the global

scope, but doing so in a local scope is probably a mistake. If they knew the

variable already existed, they would have assigned to it instead of using var.

And if they didn’t know it existed, they probably didn’t intend to overwrite

the previous one.

We can detect this mistake statically while resolving.

# lox/resolver.py Env.declare() # After checking for enclosing ... if name.lexeme in self.values: msg = "Already a variable with this name in this scope." self.error(name, msg) ...

When we declare a variable in a local scope, we already know the names of every variable previously declared in that same scope. If we see a collision, we report an error.

11 . 4 . 1Invalid return errors

Here’s another nasty little script:

return "at top level";

This executes a return statement, but it’s not even inside a function at all.

It’s top-level code. I don’t know what the user thinks is going to happen, but

I don’t think we want Lox to allow this.

We can extend the resolver to detect this statically. Much like we track scopes as we walk the tree, we can track whether or not the code we are currently visiting is inside a function declaration.

@resolve_node.register def _(stmt: Return, env: Env) -> None: if env.function_context is None: env.error(stmt.keyword, "Can't return from top-level code.") if stmt.value is not None: resolve_node(stmt.value, env)

Neat, right?

You could imagine doing lots of other analysis in here. For example, if we added

break statements to Lox, we would probably want to ensure they are only used

inside loops.

We could go farther and report warnings for code that isn’t necessarily wrong

but probably isn’t useful. For example, many IDEs will warn if you have

unreachable code after a return statement, or a local variable whose value is

never read. All of that would be pretty easy to add to our static visiting pass,

or as separate passes.

But, for now, we’ll stick with that limited amount of analysis. The important part is that we fixed that one weird annoying edge case bug, though it might be surprising that it took this much work to do it.

Challenges

-

Why is it safe to eagerly define the variable bound to a function’s name when other variables must wait until after they are initialized before they can be used?

-

How do other languages you know handle local variables that refer to the same name in their initializer, like:

var a = "outer"; { var a = a; }

Is it a runtime error? Compile error? Allowed? Do they treat global variables differently? Do you agree with their choices? Justify your answer.

-

Extend the resolver to report an error if a local variable is never used.

-

Our resolver calculates which environment the variable is found in, but it’s still looked up by name in that map. A more efficient environment representation would store local variables in an array and look them up by index.

Extend the resolver to associate a unique index for each local variable declared in a scope. When resolving a variable access, look up both the scope the variable is in and its index and store that. In the interpreter, use that to quickly access a variable by its index instead of using a map.